Tyrone N. Butts

APE Reporter

52

Honors for King reversed elsewhere DEAD LINK

www.tampabay.com

WORKING LINK

www.tampabay.com

WORKING LINK

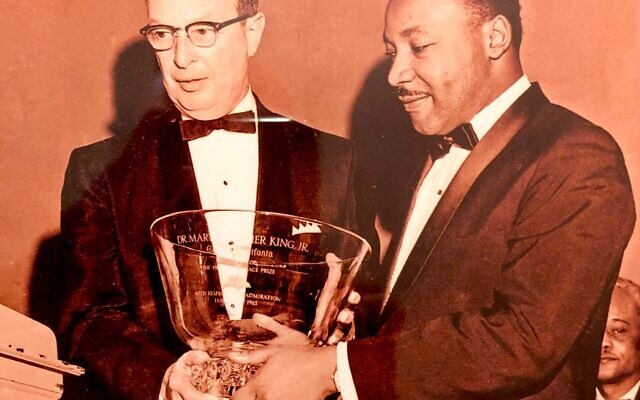

ZEPHYRHILLS - Across the country, hundreds of communities have renamed thoroughfares, created parks and set aside holidays to honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Often, there's a fight. Merchants complain about the cost of changing their letterhead and running a business on a stigmatized street.

Residents talk of inconvenience and threatened home values. Someone always raises the issue of race.

But rarely do the arguments move leaders to bring back the old name.

The Zephyrhills City Council might do just that.

ast fall, a divided City Council voted twice to rename Sixth Avenue for the slain civil rights icon. Now newly elected council member Gina King will move to restore Sixth Avenue in a meeting set for 6 p.m.

r

r

tod

y.

Although unusual, a reversal on the King na

me would not be unprecedented.

In 1979, the Alabama Legislature repealed a resolution that put King's name on a portion of interstate highway. In 1987, voters in Anchorage, Alaska, resoundingly repealed a proposal to name a new performing arts center for King.

The city of San Diego endured a six-year struggle in the late 1980s to honor King - it renamed a street, then repealed it, rejected naming an arts center, then settled on a waterfront park.

Similar controversies have swirled in communities around Tampa Bay. The present situation in Zephyrhills in many ways mirrors what happened in Tarpon Springs in 1990, when city leaders teetered on the issue after renaming a road for King. ...

***********

**

Long article and there's a lot more at the link!

T.N.B.

Honors for King reversed elsewhere

Across the country, hundreds of communities have renamed thoroughfares, created parks and set aside holidays to honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

ZEPHYRHILLS - Across the country, hundreds of communities have renamed thoroughfares, created parks and set aside holidays to honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Often, there's a fight. Merchants complain about the cost of changing their letterhead and running a business on a stigmatized street.

Residents talk of inconvenience and threatened home values. Someone always raises the issue of race.

But rarely do the arguments move leaders to bring back the old name.

The Zephyrhills City Council might do just that.

ast fall, a divided City Council voted twice to rename Sixth Avenue for the slain civil rights icon. Now newly elected council member Gina King will move to restore Sixth Avenue in a meeting set for 6 p.m.

r

r

tod

y.

Although unusual, a reversal on the King na

me would not be unprecedented.

In 1979, the Alabama Legislature repealed a resolution that put King's name on a portion of interstate highway. In 1987, voters in Anchorage, Alaska, resoundingly repealed a proposal to name a new performing arts center for King.

The city of San Diego endured a six-year struggle in the late 1980s to honor King - it renamed a street, then repealed it, rejected naming an arts center, then settled on a waterfront park.

Similar controversies have swirled in communities around Tampa Bay. The present situation in Zephyrhills in many ways mirrors what happened in Tarpon Springs in 1990, when city leaders teetered on the issue after renaming a road for King. ...

***********

**

Long article and there's a lot more at the link!

T.N.B.

Last edited by a moderator: