Rick Dean

Registered

16

http://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/local/...dlines-seminole

Seminole says schools are finally integrated

Agreement may end 35 years' federal oversight

By Dave Weber | Sentinel Staff Writer

Posted March 30, 2004

SANFORD -- When the U.S. government stepped in to demand integration of schools, no one in Seminole County dreamed it would take so long. Now, after almost 35 years of federal oversight, officials say the racism that was woven into the school system is gone.

On Monday, the School Board unanimously approved an agreement negotiated with the Department of Justice that would end court oversight of school desegregation, possibly within a few months.

Velma Williams, a Sanford city commissioner who graduated from the all-black Crooms Academy in 1959, remembers studying from torn, cast-off textbooks in shabby classrooms.

"There has been tremendous progress," said Williams, a retired Seminole Community College administrator.

"But I still have concerns. We still have to be vigilant."

While the School Board of 1970 fought integration, today's board members welcomed and praised it.

"Seminole County has come so far," School Board member Dede Schaffner said. "We have opened so many doors for so many children."

Seminole is one of several districts in Florida, including Orange, still under court desegregation orders. Orange also is seeking release from court review of its racial practices in the schools.

While Seminole is under the order, it needs court approval for changes in everything from student, faculty and staff assignments to facilities, student transportation and extracurricular activities. Every decision that affects racial makeup of the schools is weighed.

Seminole struggled to meet a series of court decrees aimed at ending

the segregation that had largely centered on Sanford schools.

The school district has been working since 1996 to be declared a "unitary" school district, one that shows no signs it once had separate schools for white and black students.

Folding black and white schools into a single "unitary" school system turned out to be complex from the beginning. It involved far more than "mixing" two historically separate racial groups, as the language of the day described it.

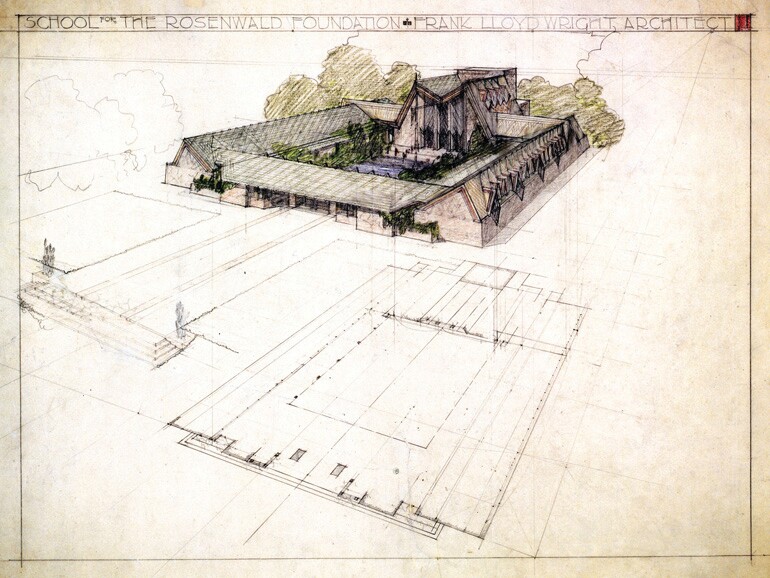

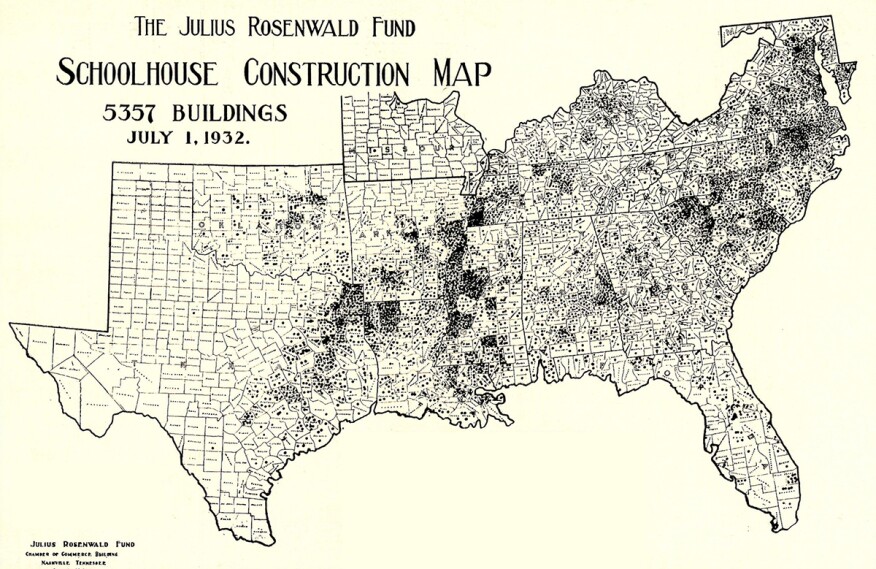

For starters, the district had five predominantly all-black schools -- Goldsboro, Rosenwald, Hopper and Midway elementaries and Crooms High.

Some were quickly integrated after the federal government intervened in 1970, but six years into the process Midway still had only nine white students and 300 blacks, according to newspaper accounts.

Goldsboro remained 67 percent black as late as 1998, when it became a districtwide magnet school focusing on math, science and technology. An influx of other races has dropped black enrollment to 32 percent.

In addition to balancing racial makeup of the schools, everything from equity in classroom construction to makeup of the high school cheerleading squad had to be addressed as officials unraveled layer upon layer of discriminatory practices that seemed innocent to some and blatant to others.

Although the old Midway school building was improved over the years, it still does not compare with many other county facilities. Superintendent Bill Vogel said the district is committed to replacing it within two years.

Officials also continue to push for more black cheerleaders, more black students in gifted

and advanced classes and fewer discipline referrals for black students.

School district and federal officials agreed in the document approved by the board Monday that the Seminole County school district has "eliminated the vestiges of segregation to the extent practicable and demonstrated its good faith commitment to the constitutional rights of all students."

The agreement now goes to U.S. District Judge G. Kendall Sharp, who will make the final decision whether the school district can be released from the desegregation order.

The School Board in 2000 agreed to additional concessions required by the Justice Department in order to get out from under federal supervision, and it adopted policies last year as commitment that it would not backslide if released from federal oversight.

Maree Sneed, a Washington, D.C. attorney representing the School Board in negotiations with the Department of Justice, said it will be up to school officials to prove that they are following the new policies. The district will make a series of reports to the community in coming years.

But board member Larry Furlong said the benefits of integration are clear, and educational opportunities for blacks and new prosperity for many are the proof.

"I don't think anyone wants to go back," Furlong said.

Dave Weber can be reached at dweber@orlandosentinel.com or

407-320-0915.

Get home delivery - up to 50% off

http://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/local/...dlines-seminole

Seminole says schools are finally integrated

Agreement may end 35 years' federal oversight

By Dave Weber | Sentinel Staff Writer

Posted March 30, 2004

SANFORD -- When the U.S. government stepped in to demand integration of schools, no one in Seminole County dreamed it would take so long. Now, after almost 35 years of federal oversight, officials say the racism that was woven into the school system is gone.

On Monday, the School Board unanimously approved an agreement negotiated with the Department of Justice that would end court oversight of school desegregation, possibly within a few months.

Velma Williams, a Sanford city commissioner who graduated from the all-black Crooms Academy in 1959, remembers studying from torn, cast-off textbooks in shabby classrooms.

"There has been tremendous progress," said Williams, a retired Seminole Community College administrator.

"But I still have concerns. We still have to be vigilant."

While the School Board of 1970 fought integration, today's board members welcomed and praised it.

"Seminole County has come so far," School Board member Dede Schaffner said. "We have opened so many doors for so many children."

Seminole is one of several districts in Florida, including Orange, still under court desegregation orders. Orange also is seeking release from court review of its racial practices in the schools.

While Seminole is under the order, it needs court approval for changes in everything from student, faculty and staff assignments to facilities, student transportation and extracurricular activities. Every decision that affects racial makeup of the schools is weighed.

Seminole struggled to meet a series of court decrees aimed at ending

the segregation that had largely centered on Sanford schools.

The school district has been working since 1996 to be declared a "unitary" school district, one that shows no signs it once had separate schools for white and black students.

Folding black and white schools into a single "unitary" school system turned out to be complex from the beginning. It involved far more than "mixing" two historically separate racial groups, as the language of the day described it.

For starters, the district had five predominantly all-black schools -- Goldsboro, Rosenwald, Hopper and Midway elementaries and Crooms High.

Some were quickly integrated after the federal government intervened in 1970, but six years into the process Midway still had only nine white students and 300 blacks, according to newspaper accounts.

Goldsboro remained 67 percent black as late as 1998, when it became a districtwide magnet school focusing on math, science and technology. An influx of other races has dropped black enrollment to 32 percent.

In addition to balancing racial makeup of the schools, everything from equity in classroom construction to makeup of the high school cheerleading squad had to be addressed as officials unraveled layer upon layer of discriminatory practices that seemed innocent to some and blatant to others.

Although the old Midway school building was improved over the years, it still does not compare with many other county facilities. Superintendent Bill Vogel said the district is committed to replacing it within two years.

Officials also continue to push for more black cheerleaders, more black students in gifted

and advanced classes and fewer discipline referrals for black students.

School district and federal officials agreed in the document approved by the board Monday that the Seminole County school district has "eliminated the vestiges of segregation to the extent practicable and demonstrated its good faith commitment to the constitutional rights of all students."

The agreement now goes to U.S. District Judge G. Kendall Sharp, who will make the final decision whether the school district can be released from the desegregation order.

The School Board in 2000 agreed to additional concessions required by the Justice Department in order to get out from under federal supervision, and it adopted policies last year as commitment that it would not backslide if released from federal oversight.

Maree Sneed, a Washington, D.C. attorney representing the School Board in negotiations with the Department of Justice, said it will be up to school officials to prove that they are following the new policies. The district will make a series of reports to the community in coming years.

But board member Larry Furlong said the benefits of integration are clear, and educational opportunities for blacks and new prosperity for many are the proof.

"I don't think anyone wants to go back," Furlong said.

Dave Weber can be reached at dweber@orlandosentinel.com or

407-320-0915.

Get home delivery - up to 50% off

Last edited by a moderator: