America's ‘Second Crusade’ in Retrospect

Looking Back at the U.S. Role in World War Two

By William Henry Chamberlin

Link:

http://www.ihr.org/jhr/v14/v14n6p22_Chamberlin.html

William Henry Chamberlin

America's Second Crusade belongs to history. Was it a success? Over two hundred thousand Americans perished in combat and almost six hundred thousand were wounded. There was the usual crop of postwar crimes attributable to shock and maladjustment after combat experience. There was an enormous depletion of American natural resources in timber, oil, iron ore, and other metals. The nation emerged from the war with a staggering and probably unredeemable debt in the neighborhood of one quarter of a

trillion dollars. Nothing comparable to this burden has ever been known in American history.

Were these human and material losses justified or unavoidable? From the military standpoint, of course, the crusade was a victory. The three Axis nations were completely crushed. American power on land and at sea, in the air and in the factory assembly line, was an indispensable contribution to this defeat.

But war is not a sporting competition, in which victory is an end in itself. It can only be justified as a means to achieve desirable positive ends or to ward off an intolerable and unmistakable threat to national security. When one asks for the fruits of victory five years after the end of the war, the answers sound hollow and unconvincing.

Consider first the results of the war in terms of America's professed war aims: the Atlantic Charter and the Four Freedoms. Here surely the failure has been complete and indisputable. Wilson failed to make his Fourteen Points prevail in the peace settlements after World War I. But his failure might be considered a brilliant success when one surveys the abyss that yawns between the principles of the Atlantic Charter and the Four Freedoms and the realities of the postwar world.

After World War I there were some reasonably honest plebiscites, along with some arbitrary and unjust territorial arrangements. But the customary method of changing frontiers after World War II was to throw the entire population out bag and baggage – and with very little baggage.

No war in history has killed so many people and left such a legacy of miserable, uprooted, destitute, dispossessed human beings. Some fourteen million Germans and people of German stock were driven from the part of Germany east of the Oder-Neisse line, from the Sudeten area of Czechoslovakia, and from smaller German settlements in Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Rumania.

Millions of Poles were expelled from the territory east of the so-called Curzon Line and resettled in other parts of Poland, including the provinces stolen from Germany. Several hundred thousand Finns fled from parts of Finland seized by the Soviet Union in its two wars of aggression. At least a million East Europeans of various nationalities Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, Yugoslavs, Letts, Lithuanians, Estonians – became refugees from Soviet territorial seizures and Soviet tyranny.

Not one of the drastic surgical operations on Europe's boundaries was carried out in free consultation with the people affected. There can be no reasonable doubt that every one of these changes would have been rejected by an overwhelming majority in an honestly conducted plebiscite.

The majority of the people in eastern Poland and the Baltic states did not wish to become Soviet citizens. Probably not one person in a hundred in East Prussia, Silesia, and other ethnically German territories favored the substitution of Polish or Soviet for German rule. What a mockery, then, has been made of the first three clauses of the Atlantic Charter: "no territorial aggrandizement," "no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned," "the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live."

The other clauses have fared no better. The restrictions imposed on German and Japanese industry, trade, and shipping cannot be reconciled with the promise "to further the enjoyment by all States, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world."

President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill sing "Onward Christian Soldiers" during their August 10, 1941, meeting on board a British battleship anchored off of Newfoundland.

In the great conflict then raging between Germany and the other Axis nations, on one side, and the British Empire and Soviet Russia, on the other, the United States was officially still neutral. Nevertheless, and violating both international law and repeated pledges to the American people, Roosevelt had already plunged the United States into the war. At this meeting he publicly committed the US to "the final destruction of the Nazi tyranny." Just weeks earlier, and on his order, US forces had occupied Iceland.

At this meeting Roosevelt and Churchill announced the "Atlantic Charter," which proclaimed "the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live." The Allied leaders were never sincere about such pledges. Britain was already violating it in the case of India and other imperial dominions, and later Roosevelt and Churchill would betray it in the case of Poland, Hungary and other European nations.

The terrific war destruction and the vindictive peace have certainly not helped to secure "for all, improved labor standards, economic advancement and social security."

In the year 1950, five years after the end of the Second Crusade, "all men in all lands" are not living "out their lives in freedom from fear and want." Nor are "all men traversing the high seas and oceans without hindrance."

The eighth and last clause of the Atlantic Charter holds out the prospect of lightening "for peace-loving peoples the crushing burden of armaments." But this burden has become more crushing than it was before the crusade took place. The "peace-loving peoples" have been devoting ever larger shares of their national incomes to preparations for war.

All in all, the promises of the Charter seem to have evaporated in a wraith of Atlantic mist.

Nor have the Four Freedoms played any appreciable part in shaping the postwar world. These, it may be recalled, were freedom of speech and expression, freedom of religion, and freedom from fear and want. But one of the main consequences of the war was a vast expansion of Communist power in eastern Europe and in East Asia. It can hardly be argued that this has contributed to greater freedom of speech, expression, and religion, or, for that matter, to freedom from want and fear.

The fate of Cardinal Mindzenty, of Archbishop Stepinac, of the Protestant leaders in Hungary, of the many priests who have been arrested and murdered in Soviet satellite states, of independent political leaders and dissident Communists in these states, offers eloquent testimony to the contrary.

In short, there is not the slightest visible relation between the Atlantic Charter and the Four Freedoms and the kind of world that has emerged after the war. Woodrow Wilson put up a struggle for his Fourteen Points. There is no evidence that Franklin D. Roosevelt offered any serious objection to the many violations of his professed war aims.

It may, of course, be argued that the Atlantic Charter and the Four Freedoms were unessential window dressing, that the war was not a crusade at all, but a matter of self-defense and national survival. However, there is no proof that Germany and Japan had worked out, even on paper, any scheme for the invasion of the American continent.

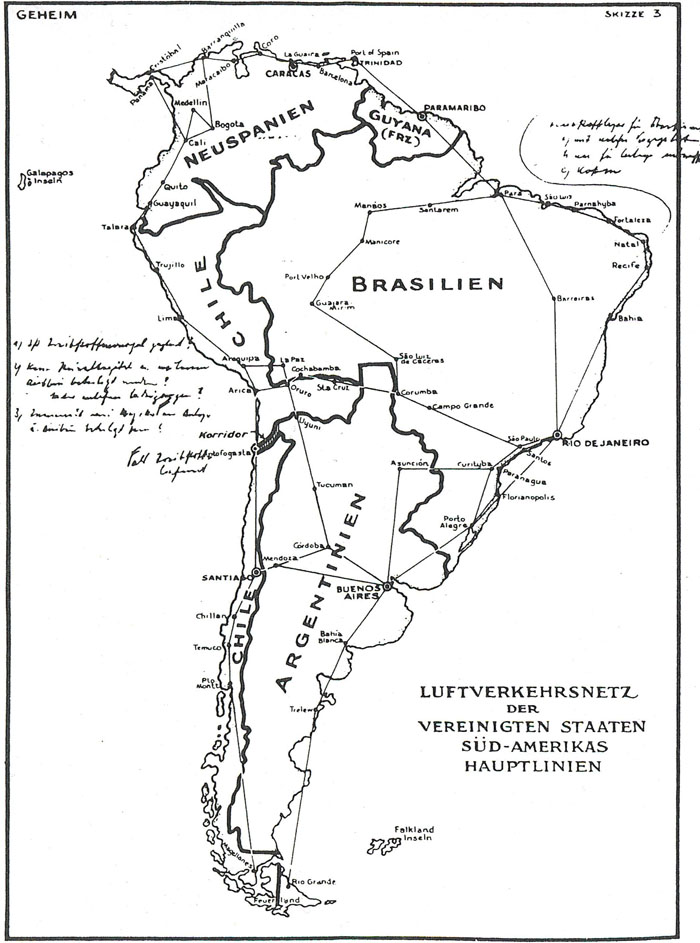

In his alarmist broadcast of May 27, 1941, Roosevelt declared: “Your Government knows what terms Hitler, if victorious, would impose. I am not speculating about all this... They plan to treat the Latin American countries as they are now treating the Balkans. They plan then to strangle the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada.”

But this startling accusation was never backed up by concrete proof. No confirmation was found even when the Nazi archives were at the disposal of the victorious powers. There has been gross exaggeration of the supposed close co-operation of the Axis powers. General George C. Marshall points this out in his

Report on the Winning of the War in Europe and the Pacific [Simon & Schuster, pp. 1-3], published after the end of the war. This report, based on American intelligence reports and on interrogation of captured German commanders, contains the following statements:

No evidence has yet been found that the German High Command had any over-all strategic plan...

When Italy entered the war, Mussolini's strategic aims contemplated the expansion of his empire under the cloak of German military success. Field Marshal Keitel reveals that Italy's declaration of war was contrary to her agreement with Germany. Both Keitel and Jodl agree that it was undesired...

Nor is there evidence of close strategic coordination between Germany and Japan. The German General Staff recognized that Japan was bound by the neutrality pact with Russia but hoped that the Japanese would tie down strong British and American land, sea and air forces in the Far East.

In the absence of any evidence so far to the contrary, it is believed that Japan also acted unilaterally and not in accordance with a unified strategic plan.

Not only were the European partners of the Axis unable to coordinate their plans and resources and agree within their own nations how best to proceed, but the eastern partner, Japan, was working in even greater discord. The Axis as a matter of fact existed on paper only. [Italics supplied.]

So, in the judgment of General Marshall, the Axis did not represent a close-knit league, with a clear-cut plan for achieving world domination, including the subjugation of the American continent. It was a loose association of powers with expansionist aims in Europe and the Far East.

Of course the United States had no alternative except to fight after Pearl Harbor and the German and Italian declarations of war. But the Pearl Harbor attack, in all probability, would never have occurred if the United States had been less inflexible in upholding the cause of China. Whether this inflexibility was justified, in the light of subsequent developments in China, is highly questionable, to say the least.

The diplomatic prelude to Pearl Harbor also includes such fateful American decisions as the imposition of a virtual commercial blockade on Japan in July 1941, the cold-shouldering of Prince Konoye's overtures, and the failure, at the critical moment, to make any more constructive contribution to avoidance of war than Hull's bleak note of November 26.

The war with Germany was also very largely the result of the initiative of the Roosevelt Administration. The destroyer deal, the lend-lease bill, the freezing of Axis assets, the injection of the American Navy, with much secrecy and double-talk, into the Battle of the Atlantic: these and many similar actions were obvious departures from neutrality, even though a Neutrality Act, which the President had sworn to uphold, was still on the statute books.

It is sometimes contended that the gradual edging of the United States into undeclared war was justified because German and Japanese victory would have threatened the security and well-being of the United States, even if no invasion of this hemisphere was contemplated. This argument would be easier to sustain if the war had been fought, not as a crusade of "a free world against a slave world," but as a cold-blooded attempt to restore and maintain a reasonable balance of power in Europe and in Asia.

Had America's prewar and war diplomacy kept this objective in mind, some of the graver blunders of the Second Crusade would have been avoided. Had it been observed as a cardinal principle of policy that Soviet totalitarianism was just as objectionable morally and more dangerous politically and psychologically than the German and Japanese brands, the course of American policy would surely have been different. There would have been more favorable consideration for the viewpoint artlessly expressed by Senator Truman when he suggested that we should support Russia when Germany was winning and Germany when Russia was winning.

It was the great dilemma of the war that we could not count on winning the war without Russia and certainly could not hope to win the peace with Russia. But there was at least a partial solution for this dilemma. One of the ablest men associated with the American diplomatic service suggested this to me in a private conversation: "We should have made peace with Germany and Japan when they were too weak to be a threat to us and still strong enough to be useful partners in a coalition against the Soviet Union."

But such realism was at a hopeless discount in a crusading atmosphere. The effect of America's policy was to create a huge power vacuum in Europe and in Asia, and to leave the Soviet Union the one strong military power in both these continents. Then the United States belatedly began to offer resistance when the Soviet leaders acted precisely as anyone might have expected them to act in view of their political record and philosophy.

An old friend whom I met in Paris in 1946, a shrewd and witty British journalist, offered the following estimate of the situation which followed the Second Crusade: "You know, Hitler really won this war – in the person of Stalin."

President Roosevelt declared in his speech of May 27, 1941: "We will accept only a world consecrated to freedom from want and freedom from terrorism." The war into which he was steadily and purposefully steering his country was apparently supposed to assure such a world.

The argument that "we cannot live in a totalitarian world" carried weight with many Americans who were not impressed by lurid pictures of the Germans (who were never able to cross the narrow English Channel) suddenly frog-leaping the Atlantic and overrunning the United States. Both in the hectic days of 1940-41 and in the cooler retrospect of 1950 it seems clear that a Nazi Germany, dominant in Europe, and a militarist Japan, extending its hegemony in Asia, would be unpleasant neighbors and would impose disagreeable changes in the American way of life.

It could plausibly be argued that in such a world we should have to assume a heavy permanent burden of armament, that we should have to keep a constant alert for subversive agents, that our trade would be forced into distorted patterns. We would be exposed to moral corruption and to the erosion of our ideals of liberty because the spectacle of armed might trampling on right would be contagious.

These dangers of totalitarianism were real enough. But it was a disastrous fallacy to imagine that these dangers could be exorcised by waging war and making peace in such fashion that the power of another totalitarian state, the Soviet Union, would be greatly enhanced.

Failure to foresee the aggressive and disintegrating role which a victorious Soviet Union might be expected to play in a smashed and ruined Europe and Asia was the principal blunder of America's crusading interventionists. Those who secretly or openly sympathized with communism were at least acting logically. But the majority erred out of sheer ignorance and wishful thinking about Soviet motives and intentions. They were guilty of a colossal error in judgment and perspective, and almost unpardonable error in view of the importance of the issues at stake.

After Pearl Harbor and the German declaration of war, the United States, of course, had a stake in the success of the Red Army. This, however, does not justify the policy of one-sided appeasement which was followed at Teheran and Yalta.

If one looks farther back, before America's hands were tied diplomatically by involvement in the conflict, there was certainly no moral or political obligation for the United States and other western powers to defend the Soviet Union against possible attacks from Germany and Japan. The most hopeful means of dealing with the totalitarian threat would have been for the western powers to have maintained a hands-off policy in eastern Europe.

In this case the two totalitarian regimes might have been expected to shoot it out to their hearts' content. But advocates of such an elementary common-sense policy were vilified as appeasers, fascist sympathizers, and what not. The repeated indications that Hitler's ambitions were Continental, not overseas, that he desired and intended to move toward the east, not toward the west, were overlooked.

Even after what General Deane called "the strange alliance" had been concluded, there was room for maneuvering. We could have been as aloof toward Stalin as Stalin was toward us. There is adequate evidence available that the chance of negotiating a reasonable peace with a non-Nazi German government would have justified an attempt, but the "unconditional surrender" formula made anything of this sort impossible. With a blind optimism that now seems amazing and fantastic, the men responsible for the conduct of American foreign policy staked everything on the improbable assumption that the Soviet Government would be a cooperative do-gooder in an ideal postwar world.

The publicist Randolph Bourne, a caustic and penetrating critic of American participation in its First Crusade, observed that war is like a wild elephant. It carries the rider where it wishes to go, not where he may wish to go.

Now the crusade has ended. We have the perspective of five years of uneasy peace. And the slogan, "We are fighting so that we will not have to live in a totalitarian world," stands exposed in all its tragic futility. For what kind of world are we living in today? It is not very much like the world we could have faced if the crusade had never taken place, if Hitler had been allowed to go eastward, if Germany had dominated eastern Europe and Japan eastern Asia? Is there not a "This is where we came in" atmosphere, very reminiscent of the time when there was constant uneasy speculation as to where the next expansionist move would take place. The difference is that Moscow has replaced Berlin and Tokyo. There is one center of dynamic aggression instead of two, with the concentration of power in that one center surpassing by far that of the German-Japanese combination. And for two reasons their difference is for the worse, not for the better.

First, one could probably have counted on rifts and conflicts of interest between Germany and Japan which are less likely to arise in Stalin's centralized empire. Second, Soviet expansion is aided by propaganda resources which were never matched by the Nazis and the Japanese.

How does it stand with those ideals which were often invoked by advocates of the Second Crusade? What about "orderly processes in international relations," to borrow a phrase from Cordell Hull, or international peace and security in general? Does the present size of our armaments appropriation suggest confidence in an era of peace and good will? Is it not pretty much the kind of appropriation we would have found necessary if there had been no effort to destroy Nazi and Japanese power?

Secret agents of foreign powers? We need not worry about Nazis or Japanese. But the exposure of a dangerously effective Soviet spy ring in Canada, the proof that Soviet agents had the run of confidential State Department papers, the piecemeal revelations of Soviet espionage in this country during the war – all these things show that the same danger exists from another source.

Moral corruption? We have acquiesced in and sometimes promoted some of the most outrageous injustices in history: the mutilation of Poland, the uprooting of millions of human beings from their homes, the use of slave labor after the war. If we would have been tainted by the mere existence of the evil features of the Nazi system, are we not now tainted by the widespread prevalence of a very cruel form of slavery in the Soviet Union?

Regimentation of trade? But how much free trade is there in the postwar world? This conception has been ousted by an orgy of exchange controls, bilateral commercial agreements, and other devices for damming and diverting the free stream of international commerce.

Justice for oppressed peoples? Almost every day there are news dispatches from eastern Europe indicating how conspicuously this ideal was not realized.

The totalitarian regimes against which America fought have indeed been destroyed. But a new and more dangerous threat emerged in the very process of winning the victory. The idea that we would eliminate the totalitarian menace to peace and freedom while extending the dominion of the Hammer and Sickle has been proved a humbug, a hoax, and a pitiful delusion.

Looking back over the diplomatic history of the war, one can identify ten major blunders which contributed very much to the unfavorable position in which the western powers find themselves today. These may be listed as follows:

(1) The guarantee of "all support in their power" which the British Government gave to Poland "in the event of any action which clearly threatened Polish independence." This promise, hastily given on March 31, 1939, proved impossible to keep. It was of no benefit to the Poles in their unequal struggle against the German invasion. It was not regarded as applicable against Russia when the Soviet Union invaded and occupied eastern Poland, with the full understanding and complicity of Hitler.

All this ill-advised guarantee accomplished was to put Great Britain and France into war against Germany, to the great satisfaction of Stalin, for an objective which the western powers could not win. Poland was not freed even after the United States entered the war and Hitler was crushed. It was only subjected to a new tyranny, organized and directed from Moscow.

There is no proof and little probability that Hitler would have attacked the west if he had not been challenged on the Polish issue. The guarantee, more than any other single action, spoiled the best political opportunity the western powers possessed in 1939. This was to canalize German expansion eastward and to keep war out of the West.

(2) The failure of the American Government to accept Konoye's overtures for a negotiated settlement of differences in the Far East. The futility of the crusade for China to which the American Government committed itself becomes constantly more clear.

(3) The "unconditional surrender" slogan which Roosevelt tossed off at Casablanca in January 1943. This was a godsend to Goebbels and a tremendous blow to the morale and effectiveness of the underground groups which were working against Hitler. It weakened the American and British position in relation to Russia, since Stalin did not associate himself with the demand. It stiffened and prolonged German resistance.

Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at the February 1945 Yalta Conference. At this meeting, the Allied coalition leaders decided the fate of millions of people around the world.

(4) The policy of "getting along" with Stalin on a basis of all-out appeasement. The Soviet dictator was given everything he wanted in the way of munitions and supplies and was asked for nothing in return, not even an honest fulfillment of the Atlantic Charter, of which he was a cosignatory. The disastrous bankruptcy of this policy is evident from one look at the geographical, political, and moral map of the world today.

(5) Failure to invade the Balkans, as Churchill repeatedly urged. This mistake was the result partly of the policy of appeasing Stalin and partly of the narrowly military conception of the war which dominated the thinking of the War Department. There was a tendency to regard the war as a kind of bigger football game, in which victory was all that mattered.

(6) The public endorsement by Roosevelt and Churchill in September 1944 of the preposterous Morgenthau Plan for the economic destruction of Germany. To be sure, the full extravagance of this scheme was never put into practice, but enough of its vindictive destructionist spirit got into the Potsdam Declaration and the regulations for Military Government to work very great harm to American national interests and European recovery.

(7) The bribing of Stalin, at China's expense, to enter the Far Eastern war and the failure to make clear, until the last moment, that unconditional sur render, for Japan, did not mean the elimination of the Emperor. These were grave mistakes, fraught with fateful consequences for American political interests in the Orient. Had the danger from Russia, the undependability of China, and the desirability of enlisting Japan as a satellite ally been intelligently appreciated, a balance of power far more favorable to the United States would now exist in East Asia.

(8) The failure, for political reasons, to exploit the military opportunities which opened up in the last weeks of the struggle in Europe, notably the failure to press on and seize Berlin and Prague. Closely linked with this error was the failure to insist on direct land access to Berlin in the negotiations about the postwar occupation of Germany.

(9) The persistent tendency to disregard the advice of experts and specialists, and base American foreign policy on "hunches" inspired by amateurs and dilettantes. Conspicuous examples of unfitness in high places were Harry Hopkins as adviser on Russia, Edward R. Stettinius as Secretary of State, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., as policy framer on Germany, and Edwin W. Pauley as Reparations Commissioner. A parallel mistake was the laxness which permitted American and foreign Communist sympathizers to infiltrate the OWI, OSS, and other important strategic agencies.

(10) The hasty launching, amid much exaggerated ballyhoo, of the United Nations. The new organization was not given either a definite peace settlement to sustain or the power which would have made it an effective mediator and arbiter in disputes between great powers. It was as if an architect should create an elaborate second story of a building, complete with balconies, while neglecting to lay a firm foundation.

These were unmistakable blunders which no future historical revelations can justify or explain away. In these blunders one finds the answer to the question why complete military victory, in the Second Crusade as in the First, was followed by such complete political frustration. Perhaps the supreme irony of the war's aftermath is that the United States becomes increasingly dependent on the good will and co-operation of the peoples against whom it waged a war of political and economic near extermination, the Germans and the Japanese, in order to maintain any semblance of balance of power in Europe and in Asia.

Primary responsibility for the involvement of the United States in World War II and for the policies which characterized our wartime diplomacy rests with Franklin D. Roosevelt. His motives were mixed and were probably not always clear, even to himself. Frances Perkins, Secretary of labor in his Cabinet and a personal friend, described the President as "the most complicated human being I ever knew."

Certainly Roosevelt was far from being a simple and straightforward character. In an age when Stalin, Hitler, and Mussolini played the role of the popular tyrant, of the dictator whose grip on his people is maintained by a mixture of mass enthusiasm and mass terrorism, Roosevelt showed what could be done in achieving very great personal power within the framework of free institutions. His career after his election to the presidency stamps him as a man of vast ambition, capable, according to Frances Perkins, of "almost childish vanity."

There were probably three principal motives that impelled Roosevelt to set in motion the machinery that led America into its Second Crusade. First was this quality of ambition. What role could be more tempting than that of leader of a wartime global coalition, of ultimate world arbiter? Second was the necessity of finding some means of extricating the American economy from a difficult position. Third was a conviction that action against the Axis was necessary. This conviction was greatly strengthened by the first two motives.

Roosevelt's first Administration, which began at the low point of a very severe depression, was a brilliant political success. He was re-elected in 1936 by an enormous majority of popular and electoral votes. But dark clouds hung over the last years of his second term of office. For all the varied and sometimes contradictory devices of the New Deal failed to banish the specter of large-scale unemployment. There were at least ten million people out of work in the United States in 1939.

The coming of the war in Europe accomplished what all the experimentation of the New Deal had failed to achieve. It created the swollen demand for American munitions, equipment, supplies of all kinds, foodstuffs which started the national economy on the road to full production and full employment.

There was the same economic phenomenon at the time of the First World War. The vast needs of the Allies meant high profits, not only for munitions makers (later stigmatized as "merchants of death"), but for all branches of business activity. It brought a high level of farm prices and industrial wages. As the Allies ran out of ready cash, loans were floated on the American market. The United States, or at least some American financial interests, acquired a direct stake in an Allied victory.

Now, the purely economic interpretation of our involvement in World War I can be pressed too far. There is neither evidence nor probability that Wilson was directly influenced by bankers or munitions makers. He had given the German Government a public and grave warning of the consequences of resorting to unlimited submarine warfare. When the German Government announced the resumption of such warfare, Wilson, with the assent of Congress, made good his warning.

Yet the lure of war profits (not restricted, it should be noted, to any single class of people) did exert a subtle but important influence on the evolution of American policy in the years 1914-17. It worked against the success of the mediation efforts launched by House as Wilson's confidential emissary. The British and French governments counted with confidence on the absence of any strong action to back up periodic protests against the unprecedented severity of the blockade enforced against Germany. The American economy had become very dependent on the flow of Allied war orders.

After the end of the war, after depression and repudiation of the greater part of the war debts, the majority of the American people reached the conclusion that a war boom was not worth the ultimate price. This feeling found expression in the Neutrality Act. Roosevelt himself in 1936 described war profits as "fools' gold."

Yet the course of American economic development in World War II followed closely the pattern set in World War I. First the Neutrality Act was amended to permit the sale of munitions. Then, as British assets were exhausted, the lend-lease arrangement was substituted for the war loans of the earlier period. As an economic student of the period [Broadus Mitchell in

Depression Decade] says:

The nation did not emerge from the decade of the depression until pulled out by war orders from abroad and the defense program at home. The rescue was timely and sweet and deserved to be made as sure as possible. Whether the involvement of the United States in the war through progressive departure from neutrality was prompted partly by the reflection that other means of extrication from economic trouble had disappeared, nobody can say. No proponent did say so. Instead, advocates of "all-out aid to Britain," convoying of allied shipping and lend-lease took high ground of patriotism and protection of civilization.

There can be no reasonable doubt that the opposition of business and labor groups to involvement in the war was softened by the tremendous flood of government war orders. It is an American proverb that the customer is always right. Under lend-lease and the immense program of domestic arms expansion the government became the biggest customer.

Ambition certainly encouraged Roosevelt to assume an interventionist attitude. He unmistakably enjoyed his role as one of the "Big Three," as a leading figure at international conferences, as a mediator between Stalin and Churchill. There is a marked contrast between Roosevelt's psychology as a war leader and Lincoln's.

The Civil War President was often bowed down by sorrow over the tragic aspects of the historic drama in which he was called to play a leading part. His grief for the men who were dying on both sides of the fighting lines was deep and hearty and unaffected. One finds little trace of this mood in Roosevelt's war utterances. There is no Gettysburg Address in Roosevelt's state papers. The President's familiar mood is one of jaunty, cocksure, sometimes flippant, self-confidence.

Another trait in Roosevelt's personality which may help to explain the casual, light-hearted scrapping of the Atlantic Charter and the Four Freedoms is a strong histrionic streak. If he originated or borrowed a brilliant phrase, he felt that his work was done. He felt no strong obligation to see that the phrase, once uttered, must be realized in action.

When did Roosevelt decide that America must enter the war? There was a hint of bellicose action in his quarantine speech of October 5, 1937. Harold Ickes claims credit for suggesting the quarantine phrase, which did not appear in earlier drafts of the speech which had been prepared in the State Department. It was like Roosevelt to pick up and insert an image which appealed to him. However, the quarantine speech met such an unfavorable reception that it led to no immediate action.

Various dates are suggested by other observers. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who enjoyed substantial influence and many contacts in Administration circles, asserted in a Roosevelt memorial address at Harvard University in April 1945: “There came a moment when President Roosevelt was convinced that the utter defeat of Nazism was essential to the survival of our institutions. That time certainly could not have been later than when Mr. Sumner Welles reported on his mission to Europe [March 1940].”

That Roosevelt may have been mentally committed to intervention even before the war broke out is indicated by the following dispatch from Maurice Hindus in the

New York Herald Tribune of January 4, 1948:

Prague – President Eduard Benes of Czechoslovakia told the late President Franklin D. Roosevelt on May 29, 1939, that war would break out any day after July 15 of that year, with Poland as the first victim, and Mr. Roosevelt, in reply to a question as to what the United States would do, said it would have to participate because Europe alone could not defeat Adolf Hitler.

A suggestion by Assistant Secretary of State A. A. Berle that Roosevelt should have become the leader of the free world against Hitler is believed to have influenced the President's psychology. [Davis and Lindley,

How War Came, p. 65.]

Admiral James O. Richardson, at that time Commander in Chief of the Pacific fleet, talked at length with Roosevelt in the White House on October 8, 1940. He testified before the Congressional committee investigating Pearl Harbor [

Report of the Congressional Joint Committee, Part I, p. 266] that he had asked the President whether we would enter the war and received the following answer:

He [Roosevelt] replied that if the Japanese attacked Thailand, or the Kra peninsula, or the Netherlands East Indies, we would not enter the war, that if they even attacked the Philippines he doubted whether we would enter the war, but that they could not always avoid making mistakes and that as the war continued and the area of operation expanded sooner or later they would make a mistake and we would enter the war.

It is clear from these varied pieces of evidence that the thought of war was never far from Roosevelt's mind, even while he was assuring so many audiences during the election campaign that "your government is not going to war." During the year 1941, as has been shown in an earlier chapter [of

America's Second Crusade], he put the country into an undeclared naval war in the Atlantic by methods of stealth and secrecy. This point was made very clear by Admiral Stark, then Chief of Naval Operations, in his reply to Representative Gearhart during the Pearl Harbor investigation:

Technically or from an international standpoint we were not at war, inasmuch as we did not have the right of belligerents, because war had not been declared. But actually, so far as the forces operating under Admiral King in certain areas were concerned, it was against any German craft that came inside that area. They were attacking us and we were attacking them.

Stark also testified that, by direction of the President, he ordered American warships in the Atlantic to fire on German submarines and surface ships. This order was issued on October 8, 1941, two months before Hitler's declaration of war.

It is scarcely possible, in the light of this and many other known facts, to avoid the conclusion that the Roosevelt Administration sought the war which began at Pearl Harbor. The steps which made armed conflict inevitable were taken months before the conflict broke out.

Some of Roosevelt's apologists contend that, if he deceived the American people, it was for their own good. But the argument that the end justified the means rests on the assumption that the end had been achieved. Whether America's end in its Second Crusade was assurance of national security or the establishment of a world of peace and order or the realization of the Four Freedoms "everywhere in the world," this end was most certainly not achieved.

America's Second Crusade was a product of illusions which are already bankrupt. It was an illusion that the United States was at any time in danger of invasion by Nazi Germany. It was an illusion that Hitler was bent on the destruction of the British Empire. It was an illusion that China was capable of becoming a strong, friendly, western-oriented power in the Far East. It was an illusion that a powerful Soviet Union in a weakened and impoverished Eurasia would be a force for peace, conciliation, stability, and international co-operation. It was an illusion that the evils and dangers associated with totalitarianism could be eliminated by giving unconditional support to one form of totalitarianism against another. It was an illusion that a combination of appeasement and personal charm could melt away designs of conquest and domination which were deeply rooted in Russian history and Communist philosophy.

The fruit harvested from seeds of illusion is always bitter.

From

The Journal of Historical Review, Nov.-Dec. 1994 (Vol. 14, No. 6), pages 22-30. Excerpted from the concluding chapter of

America's Second Crusade (1962 softcover ed., pages 337-353).

About the Author

William Henry Chamberlin (1897-1969) was an American historian and journalist.

He was born in Brooklyn, New York, and reared in Philadelphia. After high school and college education he went into journalism. His worldview as a young man was idealistic and strongly leftist. The youthful Chamberlin moved to Moscow where he served as the correspondent in Russia of the daily

Christian Science Monitor. Later he also served as Moscow correspondent of the liberal British daily

Manchester Guardian. It didn't take long for Chamberlin to lose his youthful enthusiasm for Marxism and the Bolshevik experiment. For the rest of his life, he was a bitter opponent of Communism, and particularly of the form it took in Soviet Russia.

Beginning with

Soviet Russia, a volume published in 1930, Chamberlin began writing books exposing what he regarded as the evil and fraud of Soviet Communism. His principal works about Russia in the early 1930s also included

The Soviet Planned Economic Order, which appeared in 1931, and

Russia's Iron Age, which came out in 1934. Perhaps his most impressive work was

The Russia Revolution: 1917-1921, a scholarly two-volume study first published in 1935. For years it remained the best single English-language work covering the overthrow of the Tsarist regime, the Bolshevik takeover, the Russian Civil War, and the consolidation of Soviet power.

After twelve years of outstanding work as a journalist in Soviet Russia, in 1935

The Christian Science Monitor transferred him to the Far East, from where he reported until 1939, when he was transferred to France. Following the French declaration of war against Germany, and the subsequent defeat and occupation of France, he returned to the United States.

Between 1937 and 1940 appeared additional books by Chamberlin, including

Collectivism: A False Utopia, two acclaimed books about Japan, as well as a somewhat autobiographical work,

Confessions of an Individualist. During the early 1950s he wrote a regular column for

The Wall Street Journal.

Along with many other thoughtful Americans, Chamberlin was disgusted by the role played by the United States in the Second World War. He gave eloquent and scathing voice to his bitterness in his most important work in the postwar period,

America's Second Crusade, a 372-page historical study that was originally published in 1950.